A sting for the Alan Ladd western, Shane, from Jack Schaefer’s book, announced my pending arrival. Shane is Coming, Shane is coming, Shane is here! My mother claims this was a signal element in my Christening. My father opts for the more Nationalistically appropriate association with the rebel prince of Tyrone, Shane O’Neill. I will take both. They made a film of the fictional Shane of the Wild West, which I witnessed in the local cinema, an eery experience of identification and dismay at hearing my own name whispered hugely in the crowded, dark auditorium. I was being talked about and not being talked about. I was the hero in buckskins and the outlaw dressed in black. I was the star and I was dying at sunset. Nothing like seeing your life written large on a silver screen. Our metaphysical lives were being told beyond the aural dimensions of old. Images, from distant alien sources were painting new pictures for us. The picture house in question was at the far end of Bunting Road, central to the short stub of Harty Avenue.

Bunting Road

There many venues in Dublin 12 in the fifties. Suburbs are suburbs and have long functioned as dormitories, particularly where, as with Walkinstown, there had been little or no village nucleus prior to development. There was the Moeran Hall and there was the cinema, the Apollo. Since Apollo is the Greek God of music, the name was wisely chosen. He was also leader of the Muses, and God of poetry and light. All one might require of a cinema, so. The Apollo hosted the occasional variety show with bird warblers, yodellers, hypnotists and the like. For the most part though it was Movies, Movies, Movies! The Saturday afternoon matinee was a riot of screaming kids, acting out every action scene on the way home; a swift torrent of noise flowing up Bunting Road towards the Scheme and Greenhills. All those magnificent films: The Searchers, The Magnificent Seven, The Longest Day, The Haunted House, a jumble of Westerns, World War Two drama and British farce. The cartoons kicked off with Bugs Bunny or Woody Woodpecker, romantic interludes were lustfully whistled and booed, there were the folley-n-uppers, and action heroes of such sartorial elegance as Batman and Robin. Action scenes demanded audience participation which often developed independent of the silver screen.

Harty Avenue, looking towards where the Apollo used to be.

Within the walls was mayhem. Willie the bouncer ran as tight a ship as was possible; a ship of riotous pirates all the same. Willie was The Man. In truth, he was no more than a few years older than us, a wiry youth who modelled himself on Elvis. Elvis had been a cinema usher too, back in Memphis in the early fifties, with long sideburns and oiled back hair. Not a redhead like Willie. Willie did have the occasional horde of girl screamers though. Much famed for breaking up a fight in the girls toilet, his intrusion provoking an exodus of screaming pre teens. In the retelling, his name didn’t prove too helpful to his cause.

More mature fare beckoned as we turned into teenagers towards the later sixties. The Apollo was moving towards the light. There was the weirdly perverse 2001 – A Space Odyssey with its booming opening of Richard Strauss’s Also Sprach Zarathustra, and that incongruous cosmic dance to Johann Strauss’s Blue Danube. I remember darkening stubble on my upper lip to bluff my way into the Graduate. Then there was Woodstock. I was fourteen or fifteen when the film came to the Apollo. Already, the cordite scented Rock of the late sixties had entered our blood. Our big brothers and sisters had Beatlemania, and the Rolling Stones. The Monkees were our teenybopper treat. Then came Flower Power and Freaks, free festivals of music and love. Drugs were a few steps down the road. These happy, hairy people were powered by more than a cup of Irel and a bottle of stout. They weren’t passing around Woodbines. But, the music was the message, after all.

Henry McCullough

The only Irish performer at Woodstock was Henry McCullough, guitarist with Joe Cocker’s Grease Band. Cocker was a mover and shaker, literally, in the British Blues Boom. Always a fiery performer, he was renowned for his throaty voice and his unique, spastic air guitar. At Woodstock, he performed the Beatles’ I Get By with a Little Help from My Friends.

What would you do if I sang out of tune?

Would you stand up and walk out on me?

Lend me your ears and I’ll sing you a song,

I will try not to sing out of key.

I get by with a little help from my friends!

Alvin Lee with his iconic guitar Big Red.

Another Blues Boom light, Alvin Lee of Ten Years After actually had a guitar. In the nighttime climax of the movie, Lee launched into the frenetic finale, I’m Going Home, a headbanging celebration and a trip down the memory lane of good old time Rock n Roll. And then a divine spirit materialised from the Purple Haze to play us out. Jimi Hendrix coaxed magic from his upside down guitar. Excuse me while I kiss the sky! This was a different planet altogether.

All those kids screaming their way home from the Matinee in the fifties were playing Batman or Cowboys ’n’ Indians in their heads; ten years later they were playing air guitar a la Joe Cocker, reliving the solos of Lee and Jimi Hendrix, dreaming of Rock Stars and the seductive release of sound and substance.

For years thereafter, passing down the gloom of Walkinstown Avenue, a regular tableau unfolded. With smog softening buildingd and streetlights, cloaking loitering figures in dangerous mystique, young men walked meaningfully, guitar cases slung across shoulders or held by the handle; Prohibition Era gangsters making for a hit.

The Musical Roads did not, so far as I know, yield more fledgling musicians or music stars than other more prosaically named estates. Amongst my classmates were a Frank(ie) Vaughan, and a John Lennon. Others included traditional musicians Eamon Lane and Sean O’Connell. Dublin 12 has produced an interesting spectrum of talented musicians. Fifties opera singer Dermot Troy, singer of modern folk, Rita Connolly, and that most musical ghost, our very own shadow of Jimi Hendrix, Philip Lynott. I wonder will he merit a road in his capital being named for him anytime soon. I don’t see why not.

Statue of Phil Lynott outside Bruxelles in Dublin.

In the later forties

When Diddy Levine lived with Eunice King,

He gave her the ring that she wore.

See Philip Parris Lynott, caught improbably in a sepia snap, walking the streets of Crumlin where he came to live as a child, in the fifties. All those genes jiggling there, just bursting to get out, and delivering something that is eternally the black man’s Blues, and quintessentially Irish too.

Inheritance you see,

Runs through every family,

Who is to say what is to be,

Is any better.

Over and over it goes,

The good winds and the bad winds blow,

Over and over, over and over and over …

Thin Lizzy lit a fire for a generation of Dubliners. As Beat merged with Blues Boom, a new strand of Rock was forming, merging American roots with localised experience. Kids in Dublin’s suburbs in the sixties were well in tune with this. Frank Murray, who grew up on Crotty Avenue, was one, becoming an important contributor to Dublin’s river of sound. Late in the sixties he saw a group called the Black Eagles play the Moeran Hall. Lead Eagle was Phil Lynott. They became friends and Murray went on to manage Thin Lizzy and, later the Pogues. Murray was a main mover behind the recording of Fairytale of New York, that perennial Christmas favourite from the Pogues and Kirsty McCall.

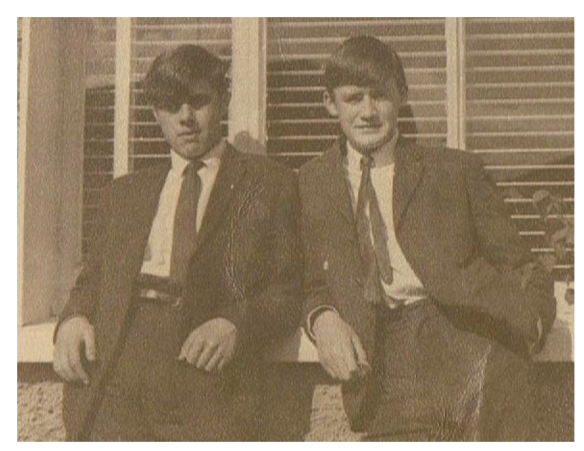

Frank Murray (right) with friend Declan Collinge on Crotty Avenue.

Christmas in Walkinstown is depicted in Youtube video: The Apollo Gang. Here Murray and friends ham it up, Beatles style, on a snowblown day in 1965 on Harty Avenue, to the refrain of the Animals’s House of the Rising Sun. This song must find a soft spot in the hearts of Walkinstown gangs. Our own crowd, hanging around the Cross, also used it, amending the lyrics to suit. There is a house in Walkinstown … to begin with, and becoming more unprintable thereafter. Yes, it’s been the ruin of many a poor boy, and (thank) God, I know I’m one.